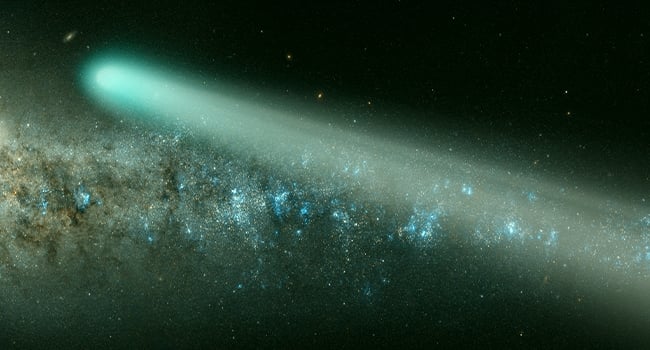

Newly discovered comet ZTF is the closest to Earth visible to the naked eye in 50,000 years and is making big headlines. Some are calling it a “super rare” and “bright green” comet, but does it live up to the hype? We explain.

Comet ZTF facts

Comet ZTF was discovered on March 2, 2022 by a robotic camera attached to a telescope called the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF). Palomar Observatory In Southern California. ZTF scans the entire northern sky every two days and captures hundreds of thousands of stars and constellations in a single shot. Many comets have been discovered with this instrument. The most recent, abbreviated C/2022 E3 (ZTF), is listed as Comet ZTF.

Why is it rare?

Comet ZTF has traveled 2.8 trillion miles and will make its closest approach to Earth in 50,000 years on February 1, 2023. Orbital calculations suggest that comet ZTF cannot return.

What makes ZTF a green comet?

The green color may be due to a molecule consisting of two carbon atoms bonded together dicarbon. This unusual chemical process is mainly confined to the head, not the tail. If you look at Comet ZTF, that greenish tint is very faint (if it’s visible). The appearance of green comets due to dicarbon is very unusual.

Recent images show that the head (coma) is distinctly green and trailed by an impressively long thin blush patch (tail). But that’s what a long exposure camera sees. The hue is much less green to the naked eye.

When and where to watch Comet ZTF

In late January to early February, the ZTF becomes bright enough to be seen by the naked eye. Use a reliable star chart to track night-to-night changes in position relative to background stars and constellations. Here are the dates and approximate locations.

January 12-14

See the constellation Corona Borealis before sunrise.

January 14-20

Look toward the Boötes constellation before sunrise.

January 21

The comet is visible in the night sky (previously only visible in the early morning). Look north, up and to the left of the Big Dipper.

January 22-25

Look closer to the constellation Draco (Dragon).

January 26-27

Look several degrees east of the Little Dipper’s bowl. On the evening of the 27th, the two outer stars in the Little Dippers bowl will be about three degrees to the upper right of the bright orange gochap.

January 29-30

Look towards Polaris.

February 1

Look closer to the constellation Camelopardalis.

February 5

Look toward the brilliant yellow-white star Capella (of the constellation Gemini).

February 6

Look directly overhead at 8pm local time, within the triangle known as “The Kids” star system in Auriga.

February 10

Look two degrees to the upper left of Mars.

Note: If you live in a large city or in the outer suburbs, seeing this comet will be difficult—if not impossible. Even for those blessed with dark and starry skies, finding the ZTF can be a challenge.

Watch Comet ZTF live now:

More information on viewing ZTF

As for tails, comets can shed two types of dust and gas. Dust tails are much brighter and more pleasing to the eye than gas tails because dust is a more effective reflector of sunlight. The most spectacular comets are dusty and can produce long, bright tails that create spectacular and impressive celestial spectacles.

Gas tails, on the other hand, appear much fainter and glow blue. The gas is activated by the sun’s ultraviolet rays, making the tail glow in the same way that black light makes phosphorescent paint glow. Unfortunately, the gas tails produced by most comets appear long, thin, and very faint; Impressive in photos but visually lacking. That’s what we’re seeing right now with ZTF.

Finally, when the ZTF is at its brightest in late January and early February, it must compete with another celestial object: the Moon. At the same time, the Moon will be near full phase (Th Full snow moon 5th February). A full moon burning the night sky like a giant spotlight will make it even more difficult to try to see a relatively faint and diffuse object like Comet ZTF.

Other visible comets

There are nearly a dozen comets to see in the sky tonight. However, most of these are only visible with moderately large telescopes. You’ll need a good star atlas and accurate coordinate positions to know where to point your instrument to see any of these. Most amateurs call such comets “dim fuzzies” because they look so beautiful through the eyelids: a faint, fuzzy blob of light. These are called “common comets”.

Every once in a while, maybe two or three times every 15 or 20 years, a bright or “big comet” comes along. These are the types that excite us, binoculars or no binoculars – all you have to do is step outside, look up and exclaim: “Oh look! That!” Such comets tend to be larger than average. Most of these have a core or core of less than two or three miles. But there are others that are many times larger.

As a general rule, the closer a comet gets to the Sun, the brighter it gets. Larger ones that pass closer than Earth’s distance from the Sun (92.9 million miles) are much brighter. Comet Hale-Pop in the spring of 1997 and comet NEOWISE (discovered by a robotic space telescope) in the summer of 2020 are good examples.

So what category does ZTF belong to? In many ways it is a very common comet, but compared to other faint obscurities, ZTF is very bright.

Related articles

Comets, Asteroids and Meteors – Difference Between Them

Join the discussion

Will you be watching the skies for the “green” comet ZTF?

Let us know in the comments below!